A salesman sells you a tube of toothpaste, claiming it will make your teeth whiter than they’ve ever been in just a week of use. It’s a bold claim, but he wins you over — for twice what you’d normally pay for toothpaste. A week later, your teeth are still yellow, and you’re tremendously ill. Not only was the toothpaste nothing special, but it was also contaminated with a nasty bacteria; apparently, it was cheaper not to sanitize the toothpaste factory equipment. Now your friends certainly won’t buy any of this not-so-miracle toothpaste, but the damage is done. You’re vomiting, and the salesman’s got your money. Herein lies the problem with the profit motive: bad behavior is profitable.

Today, to some degree, bad behavior in the pursuit of profit can be met with a lawsuit, but if indeed the world is moving towards an unregulatable, irreversible currency such as Bitcoin, we can’t rely on reactionary, punitive measures to put a band-aid on this problem; it needs a solution. Fortunately, it isn’t insurmountable. It’s a bug in the system, and bugs can be fixed. To fix a bug, you often have to dig deep to find the root of the problem, deconstructing it — and the system it exists within — to its bare essentials.

This is an article in a series on how Zacqary proposes society might debug the profit motive. This is the first article, on the bug of profitable bad behavior. The others are on the “shiny gold coin” bug, and the pressure bug.

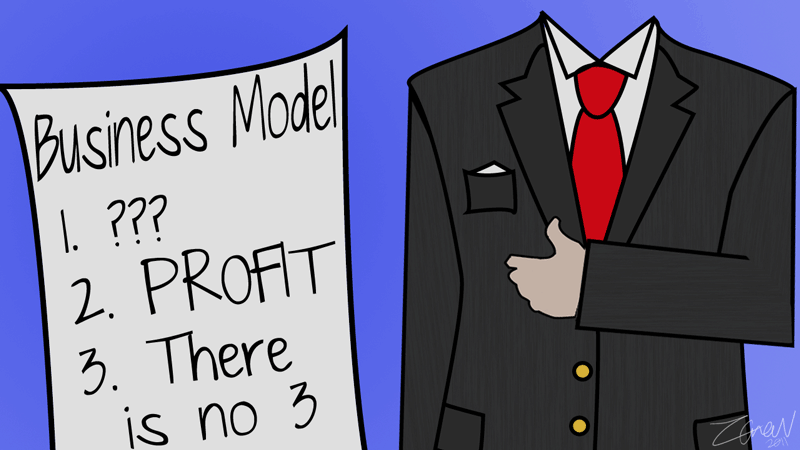

Problem: Profitable Bad Behavior

The profit motive emerges naturally in a money-based economy, because money equals power. One needs a bare minimum of money-granted power to pay for essentials (food, water, shelter), and any money beyond that grants more and more freedom: the more money you have, you can acquire more things, do more things, and get people to do more things for you. Therefore, the incentive is naturally to get as much money as possible.

Of course, as our example of the unscrupulous toothpaste salesman shows, “profit” and “good” don’t always intersect.

Solution: Regulation

The most widely implemented solution to this has been government regulation. Truth-in-advertising laws are designed to prevent, for example, the salesman’s bogus claims of miracle toothpaste. Health and safety laws require the toothpaste factory to sanitize their equipment. The penalties for breaking these laws, in theory, end up costing more than the expenses of disinfecting a factory, or coming up with a truthful marketing strategy. With well-designed, well-enforced regulations, it becomes more profitable to do the right thing.

Other laws, it should be noted, contribute to the problem. Sometimes, should a corporation do the morally right thing, it results in them making only 46 bazillion dollars in a quarter, as opposed to 47 bazillion. This would be all well and good if corporations, in most jurisdictions, weren’t legally obligated to maximize value for their shareholders, no matter what. This tends to result in the mindless pursuit of short-term profit, and total disregard for its effect on the world.

In some cases, perhaps the regulations which outlaw scummy behavior correct the problem caused by the make-money-or-die laws: they mandate the extra cost of complying (by doing the right thing), thus lowering the “maximum” amount of profit. Therefore, you could argue, that if government got out of the way entirely, businesses would be free to do the right thing of their own accord.

At which point I would argue, “Yeah, sure they would.”

In a profit-motivated system, businesses will do what’s profitable. If screwing people over is profitable, somebody’s gonna do it. This is the bug in the system.

But like lawsuits, government regulation is a kludge, a temporary workaround. Not a fix.

Problem: Coercion and Bureaucracy

Legal regulations are an ugly way of making bad behavior less profitable. They coerce businesses, with the threat of punishment, into submitting their products and practices to an often inefficient, bloated bureaucratic process, in order to enforce the regulations. This works, in the sense that a car with tree stumps instead of tires “works”, but it’s hardly desirable. More importantly than the fact that regulations require bloated bureaucracies to enforce, coercing businesses into doing things that they wouldn’t otherwise do is akin to mommy and daddy forcing you to turn off the Playstation and do your homework; it breeds contempt and resentment, so it’s no wonder that you’d say, “just five more minutes!”, or that a business would sell “meat” that’s only 35% actual beef.

Solution: Transparency

So how do we come up with a true fix for the bug of profitable bad behavior? To go back to our toothpaste salesman example, we must ask, why was his bad behavior more profitable? Simple: you didn’t know the truth until it was too late. Free market theory posits that individuals will act in their own rational self-interest, and only make trades and purchases that are beneficial. But without the truth about the salesman’s terrible toothpaste, you had no idea what your rational self-interest was.

Fortunately, the truth is easier and easier to come by every day. Wikileaks, Anonymous, and other Robin Hood-esque hacker groups expose the secrets of powerful organizations, including profit-seeking companies. Reviews of most products and services are just a Google search away. This doesn’t yet prevent bad behavior before it happens, but as it becomes increasingly more difficult to hide wrongdoing, then wrongdoing is likely to happen less and less.

Problem: Human Beings

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Free market theory posits that individuals will act in their own rational self-interest. Reality posits that people often don’t.

Even when completely aware of the truth, human beings still do irrational things. We eat at McDonald’s too much, despite knowing how caloric and non-nutritious it is. We smoke tobacco and sunbathe without sunscreen, despite knowing that it’s going to give us cancer one day. We get hideously drunk, and then drive our cars, despite knowing how dangerous it is. We buy shiny crap that we know we don’t need. We regret it all the next day, vow never to do it again, and then do it again anyway. While we can all learn to be more rational, we’re not robots. To be 100% logical and rational, every day, all the time, is asking far too much of our meaty, fleshy human brains.

The toothpaste salesman comes back to you. He’s dressed differently, cut his hair, and grown a moustache, so you don’t recognize him. This time, he sells you heroin. He comes back every week to sell you more, and you keep on buying and buying. You know that it’s killing you, but you can’t stop. The salesman doesn’t mind; he’s making lots and lots of money by exploiting your addiction to his product. The bug is not fixed. Bad behavior is profitable.

Ending government intervention might stop some businesses from pursuing amoral short-term profit, but it’s not that simple. Total, radical transparency of businesses might stop some businesses from duping and scamming their customers, but it’s not that simple. Encouraging people to be as rational as possible might help people make better decisions with their money, but it’s not that simple.

The Real Problem: Shiny Gold Coins

Like Falkvinge and many others in the pirate community, I’m fond of Bitcoin. And yet I can’t help but feel that perhaps, as a future monetary system, it too is a kludge and a workaround. For all the bugs it fixes in trade, it still falls prey to the main problem with money today: it does not, and cannot, always correlate with happiness.

Much like how measuring innovation with patents is a fallacy, today’s money — as a system of determining power — measures the wrong thing: how many shiny gold coins each individual has. Just because one individual has managed to acquire more shiny gold coins doesn’t mean they should have more power; they could have gotten those shiny gold coins by lying, cheating, and stealing, after all. Though a combination of market freedom, transparency, and rational behavior can mitigate this problem, it’s not a complete solution.

But shiny gold coins are just another bug. In part two, I’ll discuss how we might fix it.

[…] Continue reading at Falkvinge on Infopolicy /* […]

Come on. There’s plenty of companies selling toothpaste, all competing for your custom. How about you don’t buy it from some greasy snakeoil salesman you just met with absolutely zero reputation? It’s not exactly difficult to find reputable toothpaste: it’s everywhere you go! It’s so funny how statists think.

You know what’s cool about paragraphs? Sometimes, if you read beyond the first one, there are more of them.

I know. It blew my mind when I first found out too.

Reeding is harde

What blew my mind was the paragraph about the sleazy toothpaste salesman coming back with a moustache. Only this time, IT’S HEROIN.

Hahaha.

Wow, you took that literally? Ever heard of a parable?

It just takes a few bad reviews to get the judicial system on top of the bad toothpaste producer. It just gets a few angry customer’s voices out there to drive their profits to zero. I take transparency over government intervention at any moment. After all, government officials and institutions are prone to the same profit-at-any-cost behavior that motivates corporations and individuals alike, only covert, hidden, disguised under the hood of “the best for the people”.

I for one trust governments even LESS to do the right thing than every other market-driven organization. After all to get profits in the market you have to convince people to actually buy your products, not only in the short term, but in the long term as well. Government’s sneakiness gets unchecked, after all they can still force us to give them our money against our will, through taxes and inflation. They get a perpetual free pass, while companies might only get so many free rides.

I just hope more statists understand the logical falacy behind all that good-state, bad-company mindset.

Absolutely. In the section about regulation, I was assuming a (mythical) incorruptible state of maximum efficiency, so as to say that even that still wouldn’t work very well. But I feel that it goes without saying that we can’t trust traditional states too much, so I decided not to say it.

However, I do hope that more anti-statists understand the logical fallacy behind all that good-company, bad-state mindset. Any organization that grows too large and powerful is a potential problem.

But I’m getting ahead of myself — there are still two more parts to this series. ;P

Citizen driven transparency does help in quality controlling and rating of the products, services, and power wielders in a society, but it is not enough in itself, and not a very effective tool for quality control of products.

The government organized bureaucracy which you seem to criticize runs several instances whose job it is to test much of the products and some of the services in the society, to ensure they are not dangerous, and meet basic operational, environmental, and other criteria. Food is tested for bacteria, toys are tested for poison, cars are tested for safety (and drivers for driving ability), medicines are tested for side-effects, and the list goes on (even to toothpastes). This is a lot of tedious, expensive, and boring work, and not something that would be well suited for a swarm which is more driven by ideology, fun, or the latest buzz.

Now, bureaucracy is not very good at controlling strong power, and power is good at subverting bureaucracy. That’s why there are for example food additions that by right should be declared harmful (some sweeteners come to mind), proprietary and suboptimal standards accepted instead of open and simple ones (Microsofts OOXML to pick and example from software), lacking safety procedures and environment protection equipment on oil rigs (Mexican gulf disaster..), and so on.

The efforts of the swarm transparency and bugfixing should rather be directed towards the actions of large power wielders, that have and use the power to subvert governments and laws, so that captured bureaucracies can be restored to their proper function, that of keeping our environment bug-free and a nice place to live in.

Really can’t see the structural problem here. The toothpaste salesman got one packet sold, yes, and you lost a bit of money in a bad investment. He gets to keep your money, but how will that make him stand the competition against the other toothpaste manufacturers, that will keep getting your (and others who hear about it) money thereafter? He could trick some people and make some damage for a while, but he will go down. That bad investments don’t pay might be a flaw on a personal level, but not on a structural level.

Substitute “Sony” for the toothpaste salesman and “Rootkit” for the actual paste.

Or, if you like, the PS3 and hacked consumer accounts.

Or the mexican gulf oil spill, or Shell’s gushing pipeline in the Niger delta, or the neurosedyn scandal or the Pig Flu vaccine scam and so on and so forth.

Transparency is great at diagnosing a problem and informing the public but when your “toothpaste salesman” is actually a vast multibillion-dollar global corporation then it’s policy of cost-cutting can ruin the lives and livelihoods of a great many people in a very short span of time – and often get away with the profits from their behavior being far larger than the damages awarded, thus reinforcing the behavior in question. Not to mention the harm caused is oftentimes irreversible in effect.

…it follows thus that the ideal would be a situation where a corporation – or your toothpaste salesman – is from the beginning motivated to supply honest terms and decent products.

That’ll be a tough one as I myself find it hard to see a real-life situation where it would be in the interests of most corporations (or individuals out for a quick buck) to see the consumers acting out of enlightened interest.

The author of the article brings this up in light of cryptocurrency and the difficulties in seeking legal redress under situations which may occur then. I’m very interested in seeing where he’ll be taking this in part 2.

I’m really enjoying your articles, keep up the good work!

[…] profit motive. This is the second article, on the bug of shiny gold coins. The others are on the profitable bad behavior bug, and the pressure bug (coming July […]

[…] debug the profit motive. This is the third article, on the bug of pressure. The others are on the profitable bad behavior bug, and the “shiny gold coin” […]

The “profit motive” is a bad thing and is not a sufficient or necessary way of regulating most areas of human conduct. The prospect of more profit does not make for more motivation or higher performance, which is a much greater “bug” than the asshole-reward (a quite basic feature of both Capitalism and the State; there have been articles following the various politicians-in-sex-scandals, asking why power makes men pigs. That is horribly misguided, it is not necessarily the powerful position which makes them act this way, but it is the system which prioritizes egocentric, lying swindlers above honest, altruistic people, both in business and in politics).

“Therefore, the incentive is naturally to get as much money as possible.” That is horribly wrong and I love how you use the word “naturally” in order to normalise something which is not only a cultural contingency but also has brought us to the brink of apocalypse and will continue to do so as long as the myth of its natural origin is perpetuated. Not only are there studies that show that earning more than a certain amount makes you actually less happy, but common sense also shows that financial gains are neither “naturally” nor in fact practically the sole driving force behind human behaviour. Sublimation of instincts means that human behaviour is conditioned culturally to pursue a number of goals (although the goals themselves are a mere abstraction, it would be more precise to describe these as behavioural pattern. That they have an objective purpose is merely one way of interpreting them which unfortunately is preached as a physical law by misguided utilitarianists), money, political power, fame, etc. all of which are actually stand-ins for an amalgamation of the basic sex-food-rest-security scheme of animal behaviour, re-routed across our psycho-cultural landscape and hidden behind a smoke-screen of postponed gratification. There is a great video explaining how more money does not make people work harder, I will look it up once I get home.

I’m actually in complete agreement with you. Take a look at parts 2 and 3.

[…] The first article is titled Debugging the Profit Motive: Part One — Bad Behavior http://falkvinge.net/2011/07/04/debugging-the-profit-motive-part-one-bad-behavior/ […]

[…] “The profit motive emerges naturally in a money-based economy, because money equals power. One needs a bare minimum of money-granted power to pay for essentials (food, water, shelter), and any money beyond that grants more and more freedom: the more money you have, you can acquire more things, do more things, and get people to do more things for you. Therefore, the incentive is naturally to get as much money as possible.”—Zacqary Adam Green […]

Interesting article.

Please let me add that there is no law for corporations to maximize profits. If there were, they wouldn’t be allowed to pay their CEOs those ludicrous salaries.

caCA

Thirsty as ho3s

Yo what up my niggs people these days are gay af thirsty people f your claim peace madafucks

THIS IS SO WRONG

^^ Dis nikka tharsty cuhh

Zairas a little inbreotic prick that should go f her self

Where dem hooooeesss att,

FADES!!!!